I've had a few folks ask me if I can re-cane chairs and with some materials in hand, I thought I might give it a try. Alas, I soon found that I lacked the necessary tools to successfully rip out the old cane and add in the new. Instead, I decided to do what I know (upholstery, of course) and transform a dining chair with broken cane on the seat into a padded side chair. If you've got a chair in your life with broken caning or wicker that you just can't bring yourself to toss away, check out the steps below, and you too can create something marvelous and new out of what was once a dejected piece of furniture.

Above (left) is the dining chair in question. I had previously trimmed out the caning and tried to dig out the spline (this is where specific caning tools would have come in handy). What I'm left with is an open space in the seat and a groove that goes around that space which still has some caning materials in it. I'll be covering that unsightly groove up with upholstery.

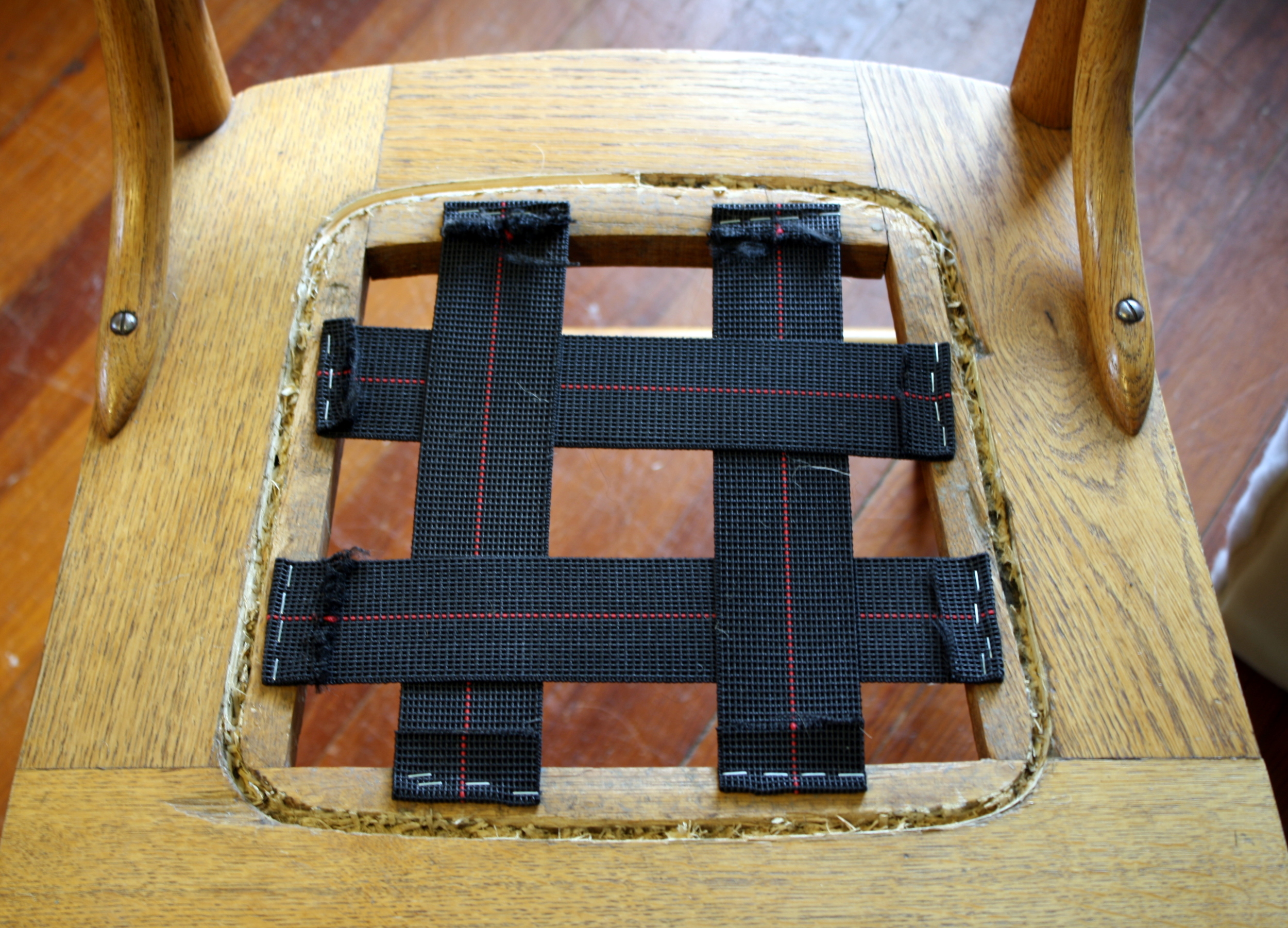

The first step is to install webbing to span the open space in the seat. The synthetic webbing I've used is strong and durable without being too rigid; it will give with the weight of a sitter, but not to the point of sinking down into the chair. To install webbing, staple down one end with two layers of staples (staple it down, then fold it over and staple again), then stretch the other end and pull it quite taut before stapling. There are specific tools available to stretch this kind of webbing, but you can also use pliers or a strong arm. Staple down the vertical pieces of webbing, then weave the horizontal pieces through.

Next, cover the scaffolding of webbing you've created with a piece of burlap. This will prevent the padding from being pushed down into the gaps between the webbing when someone sits on it and will generally create a more level and uniform seat.

For the padding I've reused a piece of chair cushion foam, though you could also use a combination of horse hair (or synthetic horse hair) and cotton batting or a thinner foam one might purchase for various crafts. I've cut this piece so that it is about a half inch wider on all sides than the groove in the chair seat where the caning spline was hammered in. While I have a tool thats specifically used for cutting foam, an electric bread knife can also do the job. Once your piece is cut, position it on the chair seat and then use a spray glue to adhere it to the burlap.

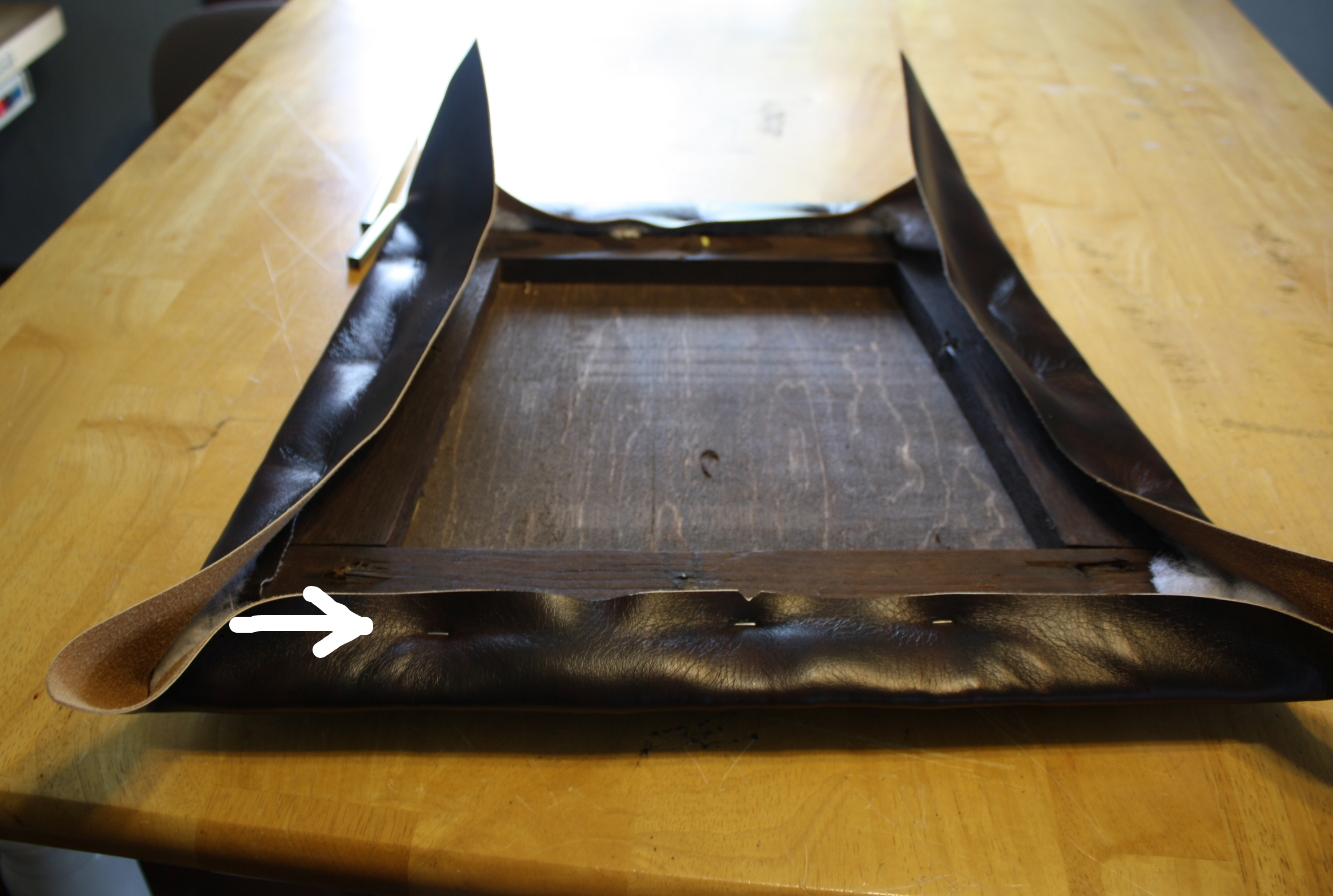

Now that the inner workings of the seat are in place, cover it with the upholstery material of your choice. I used a scrap piece of faux leather. For an in-depth explanation of how to properly attach fabric or vinyl, see my June post on how to recover a dining chair seat.

Once the fabric or vinyl is attached to your liking, trim away the excess as best you can. I'll eventually be putting decorative nails around the periphery of the seat, but first I need to cover up the ragged edge of the trimmed fabric and the staples. A plain ribbon, or a more decorative, lacy type of ribbon called gimp, could be used; I've chosen to sew up a ribbon made out of the same material that is covering the seat. To do this, I've cut a strip about 1.5" in width, folded that into thirds and top sewn down the middle of the strip.

Next, position the ribbon so that it will cover the raw edges and add the decorative nails. You can space the nails out as I've done, or drive them in in a continuous line. In addition to being evenly spaced, nail heads should be in as straight a line as possible.

Once the ribbon is down and the nail heads are all in, there should be nary a raw edge or staple in sight.

The finished product is a suave looking side chair. Not only is it made over to look more decorative than a simple caned chair, but with the webbing and padding, its also much more comfortable. Instead of sending a "broken" chair to the landfill, you've transformed it into a new piece of furniture that you can feel proud of.